WHY DO WE NEED A FEMINIST IDENTITY?

19.11.2018 / I am not a feminist, but...

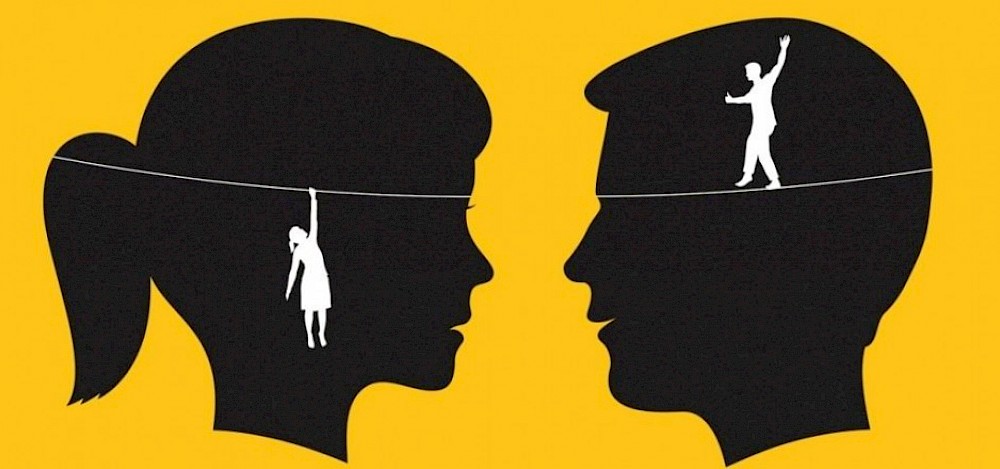

İlustrasiya www.estonianworld.com saytından götürülüb.

At an intensive summer school focused on civic education and organized by a number of European and American Universities , there was a guest trainer, whom I considered a feminist from the first moment he spoke (I later clarified that he does indeed call himself a feminist), made the following statement: “Feminism in Europe has changed a lot. These values have become our living standards, our way of life. Frankly, I do not know if we need to use our feminist identity or not”. I disagreed. I put aside the fallacy of feminism becoming a life standard for people in Europe and instead disagreed by emphasizing the importance of feminist identity.

This article is about the weak spread of the feminist identity in the socio-political life of Azerbaijan, particularly among activists and those who work on public education projects. I will discuss the difficulties and apprehension towards accepting this identity, S well as its importance and significance for us.

Questions

Violation of women’s rights in various forms is part of our daily life. At home, in the workplace, on public transport and at public venues, and in political, personal, and public life – we face discrimination, violence, and sexist language and behavior everywhere. Every day, we see headlines with words like “was beaten by boyfriend, husband or family”; “was forced to marry”; “was kidnapped”; “was raped”. All this happens so often, and with the patriarchy so deeply ingrained in our way of thinking, that we do not see this as a problem, but as a typical trait of our society and we let it go. This harsh reality, which is everywhere, makes us indifferent after a certain point towards such deep social injustice.

But when we face such cases in our socio-political life, one is surprised and cannot help but ask oneself certain questions about behavior, sexism in both thought and deed, and the various forms of patriarchal thinking by politicians and public figures. How is it possible that the same people who promote democracy and human rights, do not refrain from using sexist expressions; on top of this, instead of correcting themselves whenever criticism of this behavior is raised, they are arrogant enough to try and defend their actions? How is that possible that those who openly and directly justify violence under the guise of tradition, are still able to successfully continue their socio-political life? Why are the people, socio-political organizations, and political parties fighting for human rights and democracy fundamentally unable to solve the issue of outdated, paternalistic attitudes towards women and to form feminist values within their structures? Why it is rare to see public and political figures or socio-political organizations carry this identity proudly, declaring “I am a feminist”?

Feminists, anti-feminists, and supporters of equality

In identity research, a feminist is defined by two main and simple conditions: a) has the person mastered feminist values, and b) does s/he self-identify as a feminist?

In this discussion of feminist values, the various and sometimes confusing explanations of different waves of feminism shall be set aside. The simplest form of feminism envisages a set of cultural values, based on equal rights for women and the principle of equality of genders. Various researches pose questions about a person’s attitude towards equality between genders in the family, socio-political, professional life, personal, and public life, in order to identify whether the person accepts feminist values. If a person accepts equality and feminist identity, then s/he can be called a feminist. (Important note: this article does not seek the answer to “what is real feminism?”).

Within this framework, those who accept both the values and the identity shall be called feminists, and those who reject both shall be called anti-feminists. Also, there are those, who accept feminist values, but reject a feminist identity and say “I am not a feminist, but...”. These are categorized as supporters of egalitarian equality in feminist research.

Why do some reject a feminist identity?

Difficulties in accepting a feminist identity are not only connected with Azerbaijan. It is found all too often in many other societies, as well. Historically, when feminism first became prominent, a concurrent wave of critics began to emerge; early feminism faced harsh criticism and reproach by its opponents and media. In one word, a negative reputation of feminism can be considered historical. Many still equate feminism with “animosity towards men”, “indecency”, “immorality”, “radical movement”, “lesbianism” (particular those having an LGBT phobia) or other such notions.

But it would be naive to see these stereotypes simply as having stemmed from this historical negative reputation. Not only is feminism misunderstood by many people, but also we must remember that many people also do not accept the values promoted by feminism, and instead choose to criticize and sometimes insult them.

For example, particularly in our society, feminism is often connected closely with such concepts as “free love”, “indecency”, and “immorality”. How else could the return of authority over woman’s body from the hands of the patriarchal society to the woman herself (take into consideration that, this issue covers women virginity, freedom of movement, and so on) be perceived by a conservative man, who considers a woman to be the property of the man?! Therefore, a woman thinking like this is undoubtedly a dangerous radical to such men. It is not a coincidence that the first “question” asked of this woman is often in the vein of, “Don’t you have anyone telling you what to do?!”

Recently, we have been witnessing an increase in public criticism of sexism and violence against women in our society on Facebook and other forms of social media. We can say that certain groups adhering to feminist values have emerged. But if you ask these persons individually, very few would comfortably say “I am a feminist”. It is not easy to accept a feminist identity. A person can face criticism from his family, friends, and acquaintances about his sexuality, morality, and even his sexual orientation, and can face threats of violence themselves. In this sense, the transition from egalitarianism to feminism can often be a difficult phase for a person. The same sort of issues often arises when transitioning from passive support to activism in a social sense. So far, there are very few people who have made this transition.

I see a serious feminist discourse forming in Georgia during my visits there, particularly during meetings with activists. I met with various individuals with mixed ideological identities.

For example, a person may consider him/herself left-leaning and identifies as a leftist, but when the topic turns to gender issues, s/he can comfortably identify as a feminist as his/her second ideological identity. Similar to this there are double ideological variations such as a green-feminist, leftist-feminist, liberal-feminist, feminist-leftist, and so on. Unfortunately, in our country, it seems that the reverse is happening. Even defenders of the cause, who are actively engaged in feminist topics, try to avoid being associated with this feminist identity. Due to the issues mentioned and not mentioned above, the remaining egalitarian is more comfortable and safe.

Why is the feminist identity important?

Once we sat in a group of 7 or 8 people in a cafe in Baku; some of those gathered accepted feminist values, while others accepted the feminist identity.. One guy approached our table. As far as I understood, he knew everyone at the table, except for me. He greeted everyone with a nod and then shook hands with the men (including me) sitting around the table. When he wanted to leave, one of the females asked him, “Why didn’t you shake hands with us?” He got confused, murmured something, and then said, “I don’t know, this is Azerbaijan...” Another woman sitting at the table said “We live in Azerbaijan too...”, finishing this short dialogue.

One of the main features of such groups is the existence of general feminist correction. Non-formal, feminist friend circles generate an egalitarian atmosphere, correct language, and proper relations through the organic, non-threatening pressure of the group itself. Through continued contact in such groups, change becomes inevitable in those gathered. Personally, in terms of cleansing my speech of sexist expressions, such groups have had a more significant impact on me than any book or scholarly article.

Herein lies one of the main constraints on our socio-political life. Movements, organizations, and political parties fighting for human rights and democracy have not been able to establish meaningful feminist control mechanisms within themselves. For example, the existence of women’s councils operating within the political parties is a positive thing, but it is difficult to consider them to be feminist pressure groups that could significantly influence the internal relations and structures of the parties. Unfortunately, these women’s councils largely protect the traditional paradigms of male-female, older-younger relationships. Feminist groups that could control internal relations and language of the whole organization within a movement has, so far, failed to fully emerge in any party (of course, there is seldom criticism of this absence).

As a result of all this, the majority of people entering political parties and organizations do not change their language or views on human relations; their beliefs remain static, often totally lacking any notion of gender sensitivity. The effect of this becomes that our civil society is full of social activists and politicians using sexist expressions, thereby knowingly or unknowingly supporting various forms of discrimination and violence.

Many works on feminist identity and behaviour demonstrate that, unlike egalitarians, those who accept this identity react noticeably to sexist incidents, discrimination, and violence on the spot; they tend to intervene, read, research, and inform others about feminism and equality; and they talk about feminist issues more often in daily communication (it is noteworthy that this type of connection between identity and behavior is common among many other identities). Thus, they knowingly or unknowingly create and strengthen a feminist atmosphere. From that point of view, egalitarianism alone is unable to create feminist control mechanisms and pressure groups; there is a need for open feminist identity and, as a consequence, open feminist activism.

In such a socio-political situation…

After the wave of activism in 2011-2013, reactionary politics and pressure from public figures struck a significant blow to the discourse on democratic partnership. This has had many negative effects on civil society, but this situation may still present a small window of opportunity for ideological-social pluralism. This would create opportunities for the public, administrative, financial, and other such resources to become available to non-politicised (non-opposition) groups and groups with a weaker potential to politicize (so far) – feminists, LGBT, greens, and so on. The existing politicized, pro-democracy activism could transform into new, non-politicised groups after some time.

In that sense, it would be good if feminist groups would reevaluate the existing conditions for the mass spread of feminist identity. Maybe this situation is a historic opportunity for egalitarian critics emerging in society to transition to feminism. Certain political strategies and trending campaigns can be created for this.

Ultimately, for the formation of a feminist atmosphere and pressure groups (feminist organizations, feminist groups within other organizations, feminist control mechanisms within parties or feminization of existing women’s councils) within the civil society to transition to a feminist identity, passing this psychological and sociological phase is important. It is important to note that the increased scope of identity often leads to a decrease in public pressure on those who accept this identity. We must take this step to cleanse our socio-political life of the patriarchal, sexist ways of thinking and speaking.