AZERBAIJAN IN TRANSFORMATION INDEX BTI: STEP BACK

19.06.2018 / Index suggests lack of progress in development of democracy and market economy in the country

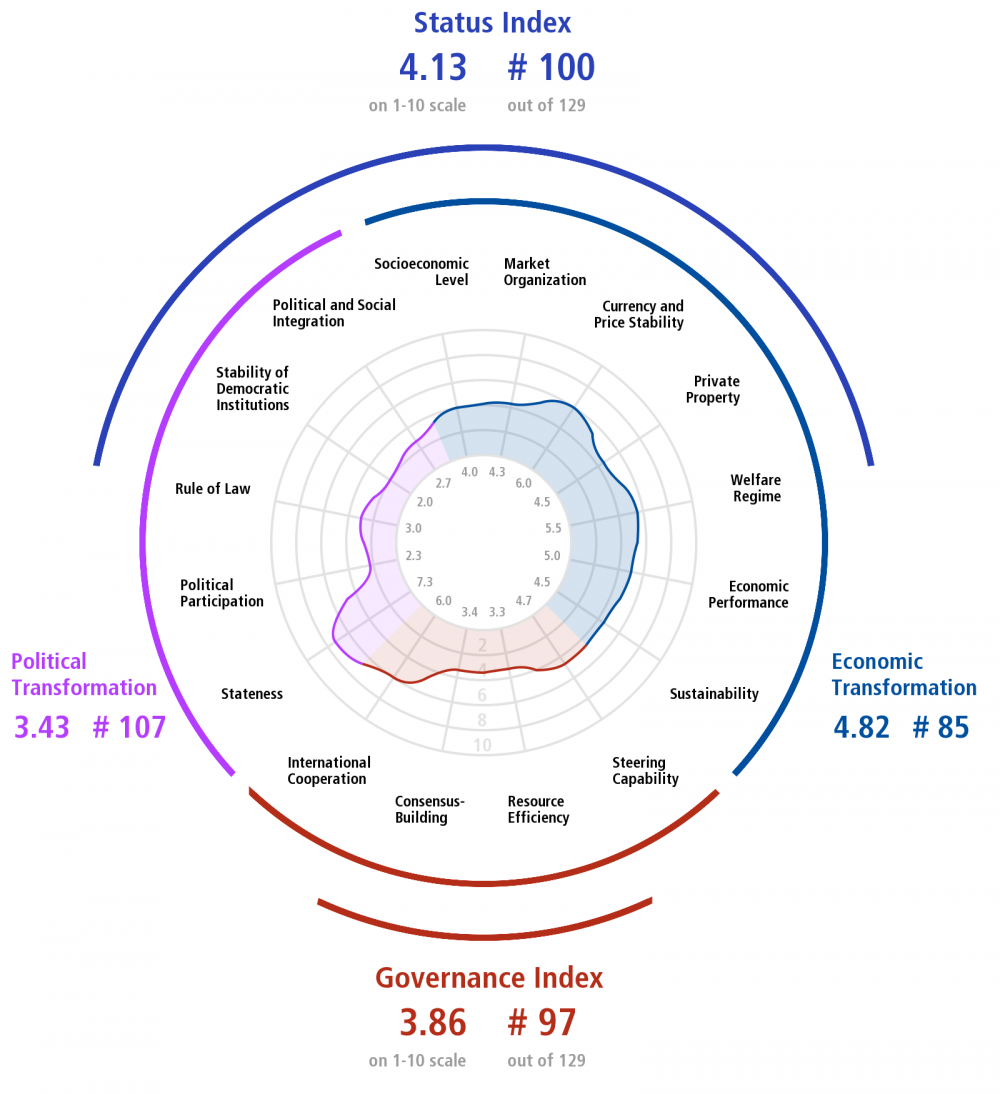

Azerbaijan is ranked 100th among 129 countries with a score of 4.13 (out of 10) in the Status Index (the aggregate of democracy and market economy scores in the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index). On the other side, the country scored 3.86 (out of 10) and ranked 97th among 129 countries in the Governance Index.

The Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) measures and how it goes about it. The BTI is made up of two rankings – the Status Index and the Governance Index. The former ranks 129 countries based on their quality of democracy and market economy, while the latter rates them according to their respective leaderships’ management performance. The focus of the BTI is countries in transition, hence the absence of Western democracies from the index. As the organization puts it, the BTI “measures successes and setbacks on the path toward a democracy based on the rule of law and a socially responsible market economy.”

The BTI takes a substantive (normative) rather than a minimalist view of what constitutes democracy and a market economy. In other words, it goes beyond commonly agreed definitions of freedom in academia, such as a regular holding of elections and rotation of leaders holding office. BTI country reports provide a more nuanced analysis of democracy’s essential requisites, such as the rule of law, stable institutions, socio-political inclusion, etc. In a similar vein, the BTI’s yardstick for measuring market economy weighs such diverse enabling factors, such as market competition, property rights, welfare regime, sustainability, etc.

Post-Soviet Eurasia

At this point, the reader may suspect that the BTI’s findings could hardly be flattering to the region’s illiberal leaders whose rise in power has gone hand-in-hand with their weakening democratic credentials. This suspicion is not ill-founded. The BTI 2018 further confirms the diverging paths countries of “post-Soviet Eurasia” had taken politically and economically since 2016 when the organization published its previous report. The BTI points to a cementing trend in the region, where the majority of the region’s countries remain firmly under the thumb of autocrats, while the outcome of the reforms in a minority of defective democracies remains far from clear. With a few exceptions (i.e. Ukraine, Georgia, Moldova and Mongolia), authoritarianism, as ever, remains the hallmark of “post-Soviet Eurasia”, as the BTI designates this region of 13 countries (on a separate note: it is long overdue to stop using “post-Soviet Eurasia”, a geopolitical misnomer, to describe the region struggling to shed its colonial past). In this regard, key political and economic trends in Azerbaijan align more or less with the bottom half of the region’s countries.

Azerbaijan’s ranking

Azerbaijan’s position in both rankings suggests that the country’s political and economic transformation has been effectively stalled. A quick comparison of country scores reveals that Azerbaijan’s performance fares badly even by regional standards (Table 1). Countries highlighted in green are the region’s best performers, while those marked in red are the worst performers in transforming institutionally and managing their transformation.

Azerbaijan is ranked 100th among 129 countries with a score of 4.13 (out of 10) in the Status Index (the aggregate of democracy and market economy scores). On the other side, the country scored 3.86 (out of 10) and ranked 97th among 129 nations in the Governance Index. Azerbaijan’s position in both rankings suggests that the country’s political and economic transformation has been effectively stalled. A quick comparison of country scores reveals that Azerbaijan’s performance fares poorly even by regional standards (Table 1). Countries highlighted in green are the region’s best performers, while those marked in red are the worst performers in transforming institutionally and managing their transformation.

If the reader compares BTI 2018, 2016 and 2014 country reports on Azerbaijan, s/he may be left with the impression that the country has been stuck in a time warp. The country’s politics has not changed much, the structure of its economy has remained more or less unaltered, and critical concerns about its governance have been left unaddressed. If anything, we witness further sliding back across major governance indicators, except for Governance Index, in which the country’s performance slightly improved.

Some additional highlights on Azerbaijan

The country report gives a rundown on the situation in Azerbaijan: while it does not offer refreshingly original commentary, it still provides insight into key developments affecting the country’s politics, economy, and governance.

In discussing the challenges to statehood in Azerbaijan, the BTI country report emphasizes potential sources of tension that may hurt the state’s monopoly of power: (1) Ethnic separatism instigated by Russia and Iran in the country’s border regions; (2) Political infighting among the country’s ruling elite that may spill over into political instability; (3) rising religious radicalism and religious’ groups filling the void left by weakened liberal-democratic CSOs. As things stand, none of those macro-environmental factors mentioned in the report appear to pose an immediate threat to the country’s sovereignty. However, the political realm is susceptible to self-fulfilling prophecies, especially, when ossified state institutions grow numb to legitimate social grievances.

The BTI emphasizes the absence of institutional checks and balances and the executive power’s control of judicial and legislative branches. Interestingly, however, the Index also stresses the constraints on the presidential power by “the entrenched interests of the state elite, the oligarchs, government ministers and other high ranking officials.” The theme of intra-elite competition has featured prominently in recent analyses of the political dynamics in Azerbaijan, and the BTI gives voice to this latest fad. The report cites state capture as the key barrier to Azerbaijan’s successful political transformation. For example, it alleges that “members of parliament are often protégés and relatives of oligarchs” and “meritocracy in the bureaucratic system is compromised by deep-rotted clientelism, cronyism, and nepotism.” In the section on the rule of law, the language used is particularly plain-spoken: parliamentarians are accused of carrying out “orders received directly from the presidential office” and courts are claimed to be “corrupt” and to “operate as a punitive mechanism in the hands of the executive power.” The report points to an apparent contradiction between government’s words and actions: on the one hand, it claims it is committed to building a democracy; on the other hand, it cracks down on critical voices.

Azerbaijan’s post-2014 economic woes add further uncertainty to the future of the country’s politics. The BTI country report on Azerbaijan refers to rallies in the regions of Azerbaijan in 2016 sparked by a sharp economic downturn and protestors’ ill-treatment in the hands of law enforcement. Although the outward manifestations of dissent have withered away since that time, the underlying sources of public grievances are still felt acutely. The BTI 2018 discusses both institutional vulnerabilities of Azerbaijan’s economy and the country’s worsening economic performance since 2014. Structural weakness includes the lack of competition, excessive dependence on oil exports, the large size of the informal economy, problems in SMEs’ access to finance, cumbersome trade regulations, economic inequality, you name it. Regarding economic performance, the report touches on the adverse impact of falling oil prices on Azerbaijan’s economy and the population’s living standards.

Concluding remarks

The BTI 2018 finds that the “social contract” based on security and stability is under increased pressure from the economic downturn, corruption, and mismanagement. As the report notes, “the future of Azerbaijan and long-term prospects for the ruling elite hinge on the progress of urgently needed reforms.” The authors do not appear to be entirely confident this is the scenario the government of Azerbaijan will embrace.